ShopDreamUp AI ArtDreamUp

Deviation Actions

Suggested Deviants

Suggested Collections

You Might Like…

Featured in Groups

Description

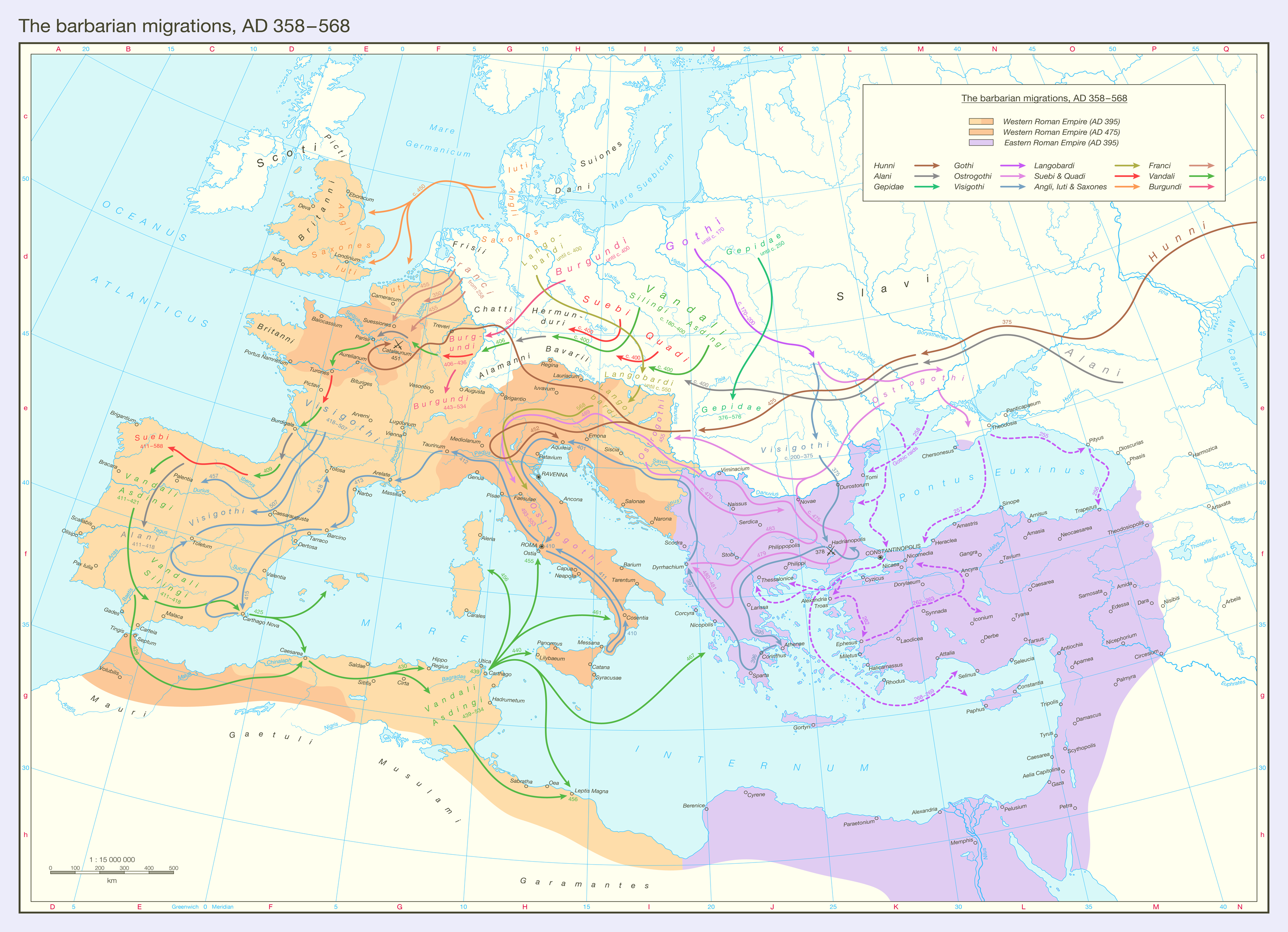

Late Antiquity was marked by the decline and division of the Roman Empire and the barbarian migrations which hastened the Roman disintegration in the west and subsequently reshaped the political face of Europe in the gradual transition from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Although these events took place over several hundreds of years, the prevailing view remains that of ruthless invasions by barbarian hordes which rapidly overwhelmed and destroyed Rome’s imperial bastion. The contemporary writers consistently believed their time to be exceptionally grim and attempted to portray it as such to future generations. Here lies the root of the unsubtle metaphors popularly associated with the barbarian migrations and the fall of the Western Roman Empire: waves of savage Huns, Goths, Vandals and the likes relentlessly besieged the frontiers of an ailing empire which ultimately washed away in a sea of blood, fire and terror. Rome’s ‘superior’ civilisation being toppled by ‘inferior’ ones was an ancient idea which ultimately found its way into the romantic perception of history during the nineteenth century and has remained remarkably popular to this very day.

In truth however, the barbarian migrations of late Antiquity roughly consisted of three different types. The first and most famous was indeed the wave of invasions into the ailing Roman Empire by confederations of barbarian tribes. The second was the gradual, mostly Roman-sanctioned settlement of the empire’s border regions by barbarian peasant-colonists. In between these two extremes existed a chaotic combination of infiltration and assimilation, of which a lowest common denominator was the Roman formation of barbarian mercenary armies to combat internal enemies and defend the imperial frontiers against other barbarians.

These three types of migration all had significant precedents in the earlier history of the Roman Empire, especially in the turmoil of the third century. Large-scale migrations in these times were only prevented by Rome’s stubborn unwillingness to accept large numbers of barbarian immigrants into the empire, assign them land and allow them de facto local autonomy. More importantly, the resurgence of Roman power under the Dominate at the end of the third century allowed for said unwillingness to be turned into an active policy of keeping barbarian tribes at bay. Barbarian meddling in the Roman world nevertheless reached a disquieting level by the mid-fourth century, a fact which can be explained by means of the so-called ‘push-and-pull’ principle.

The push factor behind the steadily increasing influx of barbarians into the Roman Empire was the enormous difference in economic potential (and therefore material wealth) between the Mediterranean dominion of the Roman Empire and the barbarian world of northern and central Europe. On the other side of the imperial frontiers, people profited little from Rome’s prosperity and where profit was to be had, it was very unevenly distributed. This initiated a long process of social polarisation, the emergence of militant barbarian nobilities with private armies and the inevitable disputes between barbarian tribes and confederations. The Romans typically encouraged such behaviour by rapidly switching alliances and playing their enemies against each other. However, this situation in the long run caused great political unrest across the barbarian world, particularly in the Lower Rhine and Danube regions. In addition to the unquenched desire for the riches of the Roman Mediterranean, the gradual militarisation of barbarian tribes eventually helped to increase the pressure upon the Roman frontiers, rather than maintain Rome’s desired status quo in the barbarian world itself.

The pull-factor is found in the gradual barbarisation of the Roman armed forces: an initially deliberate Roman policy to maintain control over the empire’s border regions which backfired completely in the end. Although Roman commanders had been enlisting barbarian mercenaries (Latin: auxilia) since the days of Julius Caesar, the barbarian component of the late Roman armies took significant proportions for two reasons. First of all, the Romans changed their military policy in the north and east from the end of the third century onward. No longer would the empire be defended by deploying heavily-armed Roman legions across the entire length of the imperial frontier. Instead, a distinction was established between the lightly-armed frontier forces (Latin: limitanei) and the heavily-armed intervention forces (Latin: comitatenses), the latter being stationed in legionary camps far away from the former. The Roman military thus greatly increased its ability to react quickly to major internal and external threats. However, this came at the cost of rendering the imperial frontiers vulnerable to unapproved infiltrations, something smaller groups of barbarians could easily take advantage off. The Romans attempted to counter this by creating buffer zones of barbarian groups with imperial permission to expand their homeland into scarcely populated, demilitarised border regions within the empire. The barbarians in return promised to defend their assigned regions for the Romans. This policy was carried out on a minor scale until the second half of the fourth century, after which the Roman government was regularly forced to accept considerable numbers of barbarians into the empire, typically having no other choice now that its military capacity was crumbling. Rome no longer had the power to continuously defend its frontiers against large groups of immigrants, let alone control them once they were allowed into the empire as ‘allies’ (Latin: foederati). The first of these ‘alliances’ (Latin: foedera) was concluded with the Salian Franks around AD 350, which gave them permission to settle in Toxandria. Nevertheless, they gradually colonised and annexed all of future Flanders and Brabant, becoming a de facto independent state within the Western Roman Empire. Such were also the consequences of similar agreements the Romans made with other barbarian groups and sub-tribes. Here lies the origin of the barbarian kingdoms which came to dominate western Europe in the fifth century.

In truth however, the barbarian migrations of late Antiquity roughly consisted of three different types. The first and most famous was indeed the wave of invasions into the ailing Roman Empire by confederations of barbarian tribes. The second was the gradual, mostly Roman-sanctioned settlement of the empire’s border regions by barbarian peasant-colonists. In between these two extremes existed a chaotic combination of infiltration and assimilation, of which a lowest common denominator was the Roman formation of barbarian mercenary armies to combat internal enemies and defend the imperial frontiers against other barbarians.

These three types of migration all had significant precedents in the earlier history of the Roman Empire, especially in the turmoil of the third century. Large-scale migrations in these times were only prevented by Rome’s stubborn unwillingness to accept large numbers of barbarian immigrants into the empire, assign them land and allow them de facto local autonomy. More importantly, the resurgence of Roman power under the Dominate at the end of the third century allowed for said unwillingness to be turned into an active policy of keeping barbarian tribes at bay. Barbarian meddling in the Roman world nevertheless reached a disquieting level by the mid-fourth century, a fact which can be explained by means of the so-called ‘push-and-pull’ principle.

The push factor behind the steadily increasing influx of barbarians into the Roman Empire was the enormous difference in economic potential (and therefore material wealth) between the Mediterranean dominion of the Roman Empire and the barbarian world of northern and central Europe. On the other side of the imperial frontiers, people profited little from Rome’s prosperity and where profit was to be had, it was very unevenly distributed. This initiated a long process of social polarisation, the emergence of militant barbarian nobilities with private armies and the inevitable disputes between barbarian tribes and confederations. The Romans typically encouraged such behaviour by rapidly switching alliances and playing their enemies against each other. However, this situation in the long run caused great political unrest across the barbarian world, particularly in the Lower Rhine and Danube regions. In addition to the unquenched desire for the riches of the Roman Mediterranean, the gradual militarisation of barbarian tribes eventually helped to increase the pressure upon the Roman frontiers, rather than maintain Rome’s desired status quo in the barbarian world itself.

The pull-factor is found in the gradual barbarisation of the Roman armed forces: an initially deliberate Roman policy to maintain control over the empire’s border regions which backfired completely in the end. Although Roman commanders had been enlisting barbarian mercenaries (Latin: auxilia) since the days of Julius Caesar, the barbarian component of the late Roman armies took significant proportions for two reasons. First of all, the Romans changed their military policy in the north and east from the end of the third century onward. No longer would the empire be defended by deploying heavily-armed Roman legions across the entire length of the imperial frontier. Instead, a distinction was established between the lightly-armed frontier forces (Latin: limitanei) and the heavily-armed intervention forces (Latin: comitatenses), the latter being stationed in legionary camps far away from the former. The Roman military thus greatly increased its ability to react quickly to major internal and external threats. However, this came at the cost of rendering the imperial frontiers vulnerable to unapproved infiltrations, something smaller groups of barbarians could easily take advantage off. The Romans attempted to counter this by creating buffer zones of barbarian groups with imperial permission to expand their homeland into scarcely populated, demilitarised border regions within the empire. The barbarians in return promised to defend their assigned regions for the Romans. This policy was carried out on a minor scale until the second half of the fourth century, after which the Roman government was regularly forced to accept considerable numbers of barbarians into the empire, typically having no other choice now that its military capacity was crumbling. Rome no longer had the power to continuously defend its frontiers against large groups of immigrants, let alone control them once they were allowed into the empire as ‘allies’ (Latin: foederati). The first of these ‘alliances’ (Latin: foedera) was concluded with the Salian Franks around AD 350, which gave them permission to settle in Toxandria. Nevertheless, they gradually colonised and annexed all of future Flanders and Brabant, becoming a de facto independent state within the Western Roman Empire. Such were also the consequences of similar agreements the Romans made with other barbarian groups and sub-tribes. Here lies the origin of the barbarian kingdoms which came to dominate western Europe in the fifth century.

By the end of the fourth century, the foedera had become little more than vulgar mercenary contracts. Thus the Romans not only lost the nominal authority over their barbarian ‘subjects’ but also owed them financial compensation. More importantly, a foedus (sg.) could henceforth be applied to the entire empire, not just the lightly populated frontier areas. The leaders of these barbarian mercenary armies – for such they had become – typically attempted to use their status as foederati to gain a high rank in the Roman military, both to strengthen their prestige amongst their peers and to secure their payments now that the Roman economy was falling apart in the west. A notable example of this was Childeric, leader of the Salian Franks (r. AD 457 – 481), who held the Roman equivalent rank of a general (Latin: magister) and already considered himself a veritable king (Latin: rex). Rome’s growing reliance on the foedera-system was closely connected to the problems caused by the expansion of the Roman military under Diocletian (r. AD 284 – 305). For lack of actual Romans, the recruitment of barbarians into the regular Roman legions increased significantly and some barbarian officers inevitably rose through the ranks all the way to the Roman high command. The de facto ruler of the Western Roman Empire was often not the emperor but a barbarian general. Notable examples were the Vandal Stilicho, who commanded the western imperial forces from the death of Theodosius the Great in AD 395 to his own death in AD 408, and Odoacer, who deposed the last Western Roman emperor in AD 476 and named himself rex gentium of the Italian peninsula. Meanwhile in the Eastern Roman Empire, the Alan Aspar held the supreme command over the armies of Constantinople for forty years until AD 471.

Hostility towards barbarians was a common attitude among the Romans, especially in the east. The civilian branch of the imperial government in Constantinople, which had hardly been infiltrated by barbarians, frequently condemned the barbarisation of the armed forces. In his speech ‘On Kingship’ (Latin: De Regno), orator Synesius of Cyrene openly advised the Eastern Roman emperor Arcadius to stop using ‘wolves as watchdogs’ and purge the military of barbarians before it was too late. Such criticism was indeed justified, considering what was happening in the west: the foedera-policy caused ever more barbarians to cross the imperial frontiers and their boldness grew according to their numbers. As the fifth century progressed, the western empire could do little more than trying to play the barbarians against each other with two-faced diplomacy and divide-and-conquer strategies while holding on to the Roman heartland in Italy. These policies nevertheless came at the cost of leaving entire regions in chaos and only served to put off the inevitable. On top of this, the western empire almost literally stabbed itself to death with ruthless paranoia and infighting. Leaders of power and ability like Stilicho (d. AD 408), Bonifacius (d. AD 432), Aetius (d. AD 457) or Majorian (d. AD 461) all died at the hands of their jealous rivals in the imperial elite, making the empire’s disintegration and the barbarian take-over all the easier…

===================

Image size

3000x2171px 2.61 MB

© 2014 - 2024 Undevicesimus

Comments44

Join the community to add your comment. Already a deviant? Log In